Richard Whately

Why?

Hayek, Mises and others: did they say "we recognise Whately's insight into 'by human creation but not human design', into the dangers of interference whether from benevolent aims or no - but we reject his appeals to Godly Providence"?

Or is there more to it than that? The parallels are so strong, so many of the features align, it's difficult not to think they kept the nature of Providence right in there.

Why is that important? I think the answers lie somewhere in both their shared blindness to other sources of social operating systems (especially if looking at 'uncivilised' societies) and their fundamental, religious reverence toward the order they believe they see. Arguably Hayek's is even stronger than Whately's - he wants to impose it on others, to educate out of them any residual 'anachronistic' altruism in service of that religion.

Some background

I got to Whately via this wikipedia page on 'catallactics' - MIses and Hayek cite him as their source for the term. But after reading into Whately's thinking more, I'm struck by how much else from his work clearly informed Hayek (though Hayek himself doesn't cite him much).

Born in the late 1700s and living through to the mid 1800s (wikipedia), I find Whately fascinating for his combination of sincere, dogged work on thinking rationally combined with 'scientific' examination of his religious beliefs and of the church's ideas at that point. The result is a weird, flavourful cocktail - and crucially, I think you can see some of that cocktail later in Hayek, though Hayek insists on the secular, evolved nature of his ideas.

Whately is - I think - a tad too early to have been fully immersed in the fallout from Darwinism and the any geological "hang on, this rock is reeeeaallly old" stuff going on at the time. (Though there's overlap).

Also (wikipedia again):

In Oxford his white hat, rough white coat, and huge white dog earned for him the sobriquet of the White Bear.

That's quite an image.

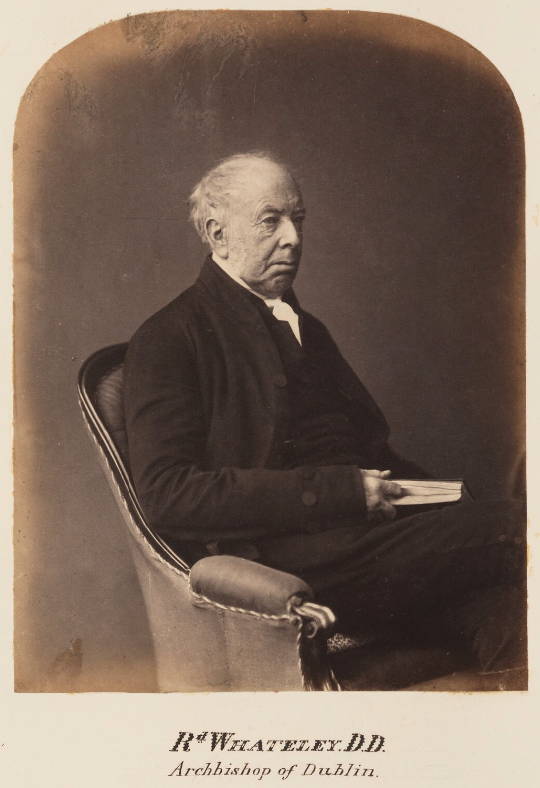

This is him in his last decade, via the National Portrait Gallery. (This illustration might be closer to his white attire.)

'Introductory Lectures on Political Economy' (1831)

It's in his 'Introductory Lectures on Political Economy' (online version here) - delivered "Easter term MDCCCXXXI" (1831) at the University of Oxford that I've found the good stuff. Notes and thoughts on that below, and then we can see what questions come out of that. Page numbers for the printed version I'm working from differ from the online one a bit - add 9 pages for online.

Lecture IV, pp.90.

-

Begins with a basic question - what's the nature of the 'social union' that humans seem to need? He rejects that it's ever been by human design (echoing Cicero and Aristotle).

- "... By nature a social being, incapable, except in a community, of exercising or developing his most important and the most characteristic faculties." 91

-

First statement that people appear to be serving some larger social purpose unknown to them 'while pursuing some immediate personal gratification'.

- Sees this as a kind of instinct: "In many cases we are liable to mistake for the wisdom of Man what is in truth the wisdom of God." 92

-

His analogy is with the physical body: "In the bodily structure of Man we plainly perceive innumerable marks of wise contrivance, in which it is plain that Man himself can have had no share."

- So with the social tissue that connects us; both can have arisen from 'the wisdom of god'. But reading on, I don't think his view can be dismissed purely as 'god made all this' - it's more nuanced than that. 'God made it' is part of it, but what he means by that - or his view of what Providence / made by God means - needs more pinning down, if we're to get a grip on how these ideas might have affected later thinking (or been a reflection of their time).

-

A more fleshed out body parallel - and a 'means nowhere devised consciously' statement: "But when human conduct tends to some desirable end, and we are competent to perceive that the end is desirable, and the means well adapted to it, we are apt to forget, that in the great majority of instances, those means were not devised, nor those ends proposed, by the persons who were the actual agents. Those who build and who navigate a ship, have usually, I conceive, no more thought about the national wealth and power, the natural refinements and comforts, dependent on the interchange of commodities, and the other results of commerce, than they have of the purification of the blood in the lungs by the act of respiration, or than the bee has of the process of constructing a honeycomb." 92/3

- The bee making the honeycomb / the human piloting the ship, both equally is ignorant of the larger goal.

-

A consequence of this - if society relied purely on benevolence and good feeling, "society I fear would fare ill". And his argument is then pure Hayek:

-

Relying on that good will for the glue that makes the social union and its outcomes "implies, not merely benevolent feelings stronger than, in fact, we commonly meet with, but also powers of abstraction beyond what the mass of mankind can possess.” 93 Those italics are in the original. It’s exactly the limits to knowledge arg. “As it is, many of the most important objects are by the joint agency of persons who never think of them, nor have any idea of acting in concert; and that, with a certainty, completeness, and regularity, which probably the most diligent benevolence under the guidance of the greatest human wisdom could never have attained."

- So it would have been impossible for humans to create society through conscious action - and a key reason is that humans cannot muster the 'powers of abstraction' necessary.

- This is Ferguson also - the "result of human action but not the execution of any human design" - but with an explanation much closer to what Hayek says much later on. Identical? Let's see what happens with how it's tangled with his religious views.

-

Then a repeat of the common economic allegory - the 'head-commissary entrusted with the office of furnishing to this enormous host their daily rations' - versus the reality of London somehow feeding itself. 94

- In Head Commissary allegory let's mull what institutions like the supermarket say about these older stories. Whately himself suggests army supplies partly manage it, but their uniformity and lack of variety make them tractable.

-

This is great on people embedded in a system not able to see its complexity (and also hints at Hayekian treatment of people thinking they can meddle): "Early and long familiarity is apt to generate a careless, I might almost say, a stupid, indifference, to many objects, which, if new to us, would excite a great and a just admiration; and many are inclined even to hold cheap a stranger, who expresses wonder at what seems to us very natural and simple, merely because we have been used to it; while in fact perhaps our apathy is a more just subject of contempt than his astonishment. Moyhanger, a New-Zealander who was brought to England, was struck with especial wonder, in his visit to London, at the mystery, as it appeared to him, how such an immense population could be fed, as he saw neither cattle nor crops. Many of the Londoners, who would perhaps have laughed at the savage's admiration, would probably have been found never to have even thought of the mechanism which is here at work." 96/7